A love letter to the future

It’s time to retire the old savior storyline. Real change should come from shared authorship, trust, and listening. When stories grow from lived experience, they don’t just describe a better future; they start to feel like a love letter to it.

Ever since I was a little girl, packing crayons and old toys into a shoebox for a child I’d never meet, I’d been handed a familiar story about what it means to “do good.” You’re helping people far away, I was told, people who have less than we do here. That narrative wasn’t statistically wrong; being born in the Western world does come with financial privilege. But the story itself was thin.

A world neatly divided into those with problems and those with solutions, a world of givers and receivers, of problems and rescuers. It’s a framing with deep roots, shaped in part by old colonial ideas about who leads, who follows, and whose voice matters. It was simple, attention-grabbing… and most importantly, it raised money. But it also reinforces power imbalances, centred the wrong voices, and flattened the very people and places it claimed to serve.

We’re long overdue for a narrative shift.

Perhaps a shift from stories about what’s broken to stories about what’s being built?

Over the past decade, design practice in the social impact space has started to stretch. Exploring participatory methodologies, rethinking the relationships with beneficiaries, and even their governance models or ways of operating. And although these approaches are still far from the norm, the ambition behind them should be reflected in how we tell stories, too.

Many of our narratives still stay stuck in the language of urgency, rescue, and lack. The old arcs, problem, victim, savior, seem to be a misfit for the practice that is taking shape. A practice that realises nobody is waiting for heroes, and deep collaboration is what is needed. What is collapsing isn’t just a model of charity, but a way of seeing, understanding, and relating to the work.

So, how does that relate to storytelling?

Stories don’t just get passed on; they move through people and places, shifting as they go. They travel through networks, conversations, media, institutions, and in that movement, they gather shape and force. Each time a story is told, it carries traces of the context it came from and leaves impressions on the one it reaches next. Over time, those stories begin to organize how we see the world and each other. They influence what we think is normal, what we treat as true, and what we believe is possible. Sociologists sometimes describe this as stories acting like small social systems, circulating power, values, and meaning.

But when we keep telling stories about crisis, urgency, and rescue, our ways of working start to mirror them: rushed, top-down, focused on fixing rather than listening. Stories don’t just describe the world; they take part in building it. And therefore play an essential role in transforming the industry.

We need more stories of agency, creativity, and persistence, not to inspire from a distance, but to prototype new patterns of trust, care, and reciprocity. Narrative is a kind of cultural technology: it makes certain futures legible, others invisible. When we treat a story as a material, something to shape, test, and learn through, we might be able to shape systems we’ve been unable to.

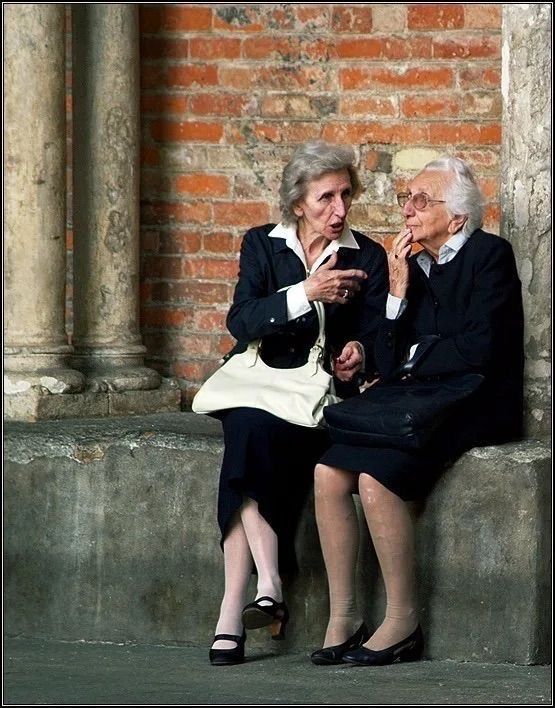

Letting lived experience lead

Recently, I worked on a project where an NGO explored what it would mean for their shareholders to own their own data, stories, and information. An obvious right, but new for the sector.

We explored what that could mean in practice. What would a shareholder-owned studio look like? What kinds of stories might grow when authorship and ownership come directly from those living the experience? What would social impact narratives look like today if people had a choice which parts of their story to share, and which not to? The future doesn’t need to be about perfect stories at all; there’s beauty in human struggle, too, but stories in all cases should be an expression of agency.

Stories which are a result of expressions of agency might look like;

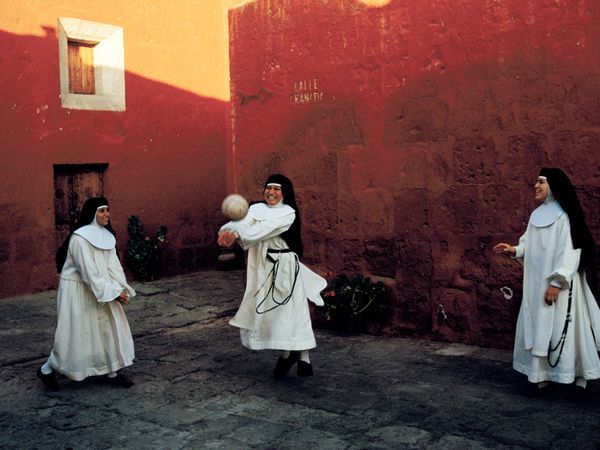

- Redistributing authorship through early, facilitated gatherings like listening sessions that begin by hearing what matters to a community,

- or story labs, which might look like creative spaces where participants shape how their own experiences are represented.

- Projects that share ownership of the story itself, not just its outcomes, with consent and creative control built into the process from the start.

- Story formats that invite participation, pieces that grow through reflection and exchange rather than production value alone.

When authorship and ownership shift, the work gains depth. It reflects the realities of the people it represents, not assumptions about them. Shifting authorship changes more than narrative; it changes the structure of the work itself. Decisions start to move closer to those most affected by them. That changes how teams plan, and institutions listen, and ultimately, what success of campaigns looks like. The work stops chasing visibility and starts building trust. It becomes accountable to the people inside the story.

The shift is taking place

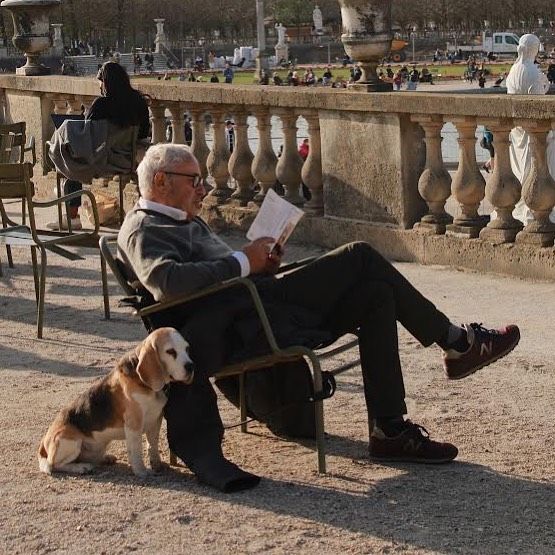

You can see it in practice. Social organisations are experimenting with circular, community-led models, cooperatives, creative enterprises, and shared platforms where voice and value come together. Funders are beginning to follow, maybe testing multi-year, trust-based partnerships that give grantees more autonomy. These aren’t isolated cases; they’re early signals of a deeper change. The logic of control is giving way to one of relationship. The system is hopefully learning that trust is not a by-product of good work but a condition that makes it possible.

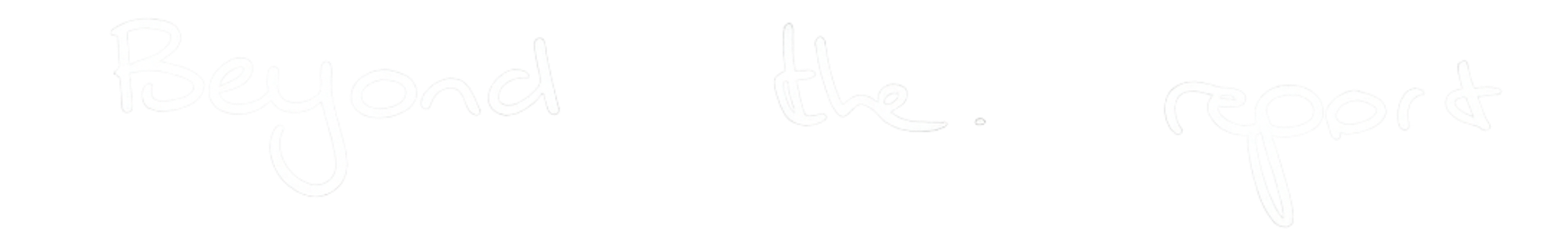

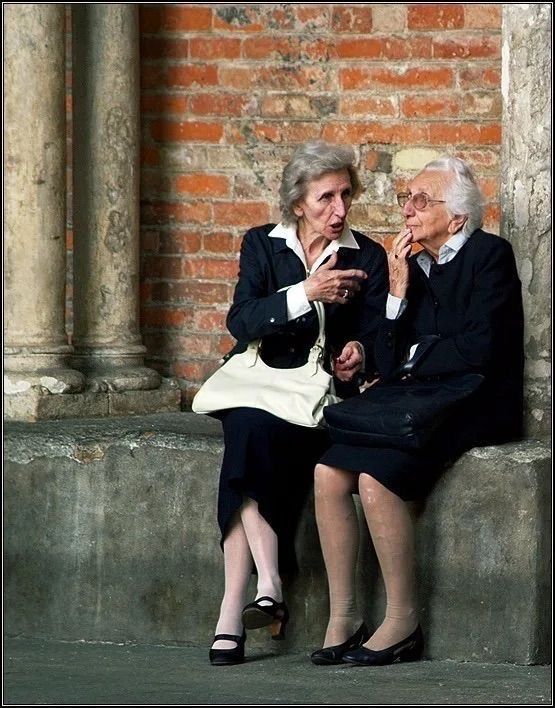

Storytelling is part of that same shift. In documentary and across other forms, we’re seeing stories built through collaboration rather than observation, a tool for connection. Meaning is shaped between people. These new narratives hold the world’s complexity, asking audiences to hold responsibility for what they see. Each story carries a glimpse of the future inside it, a small structure of how cooperation might feel, how care might look when it’s built into the process itself.

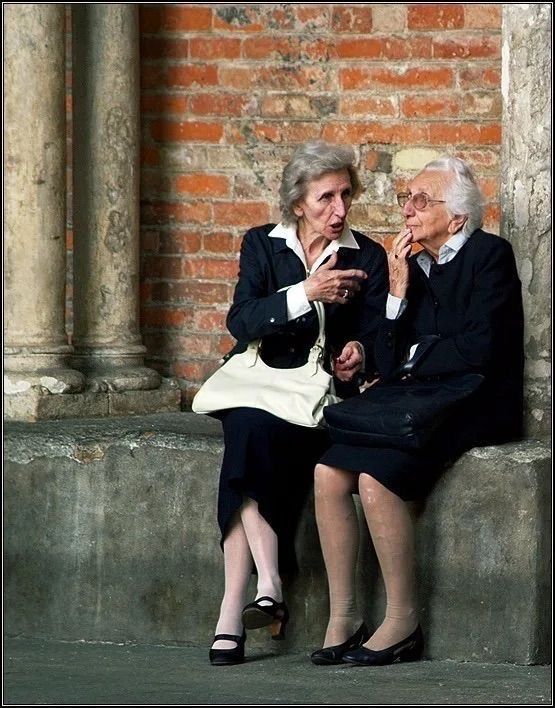

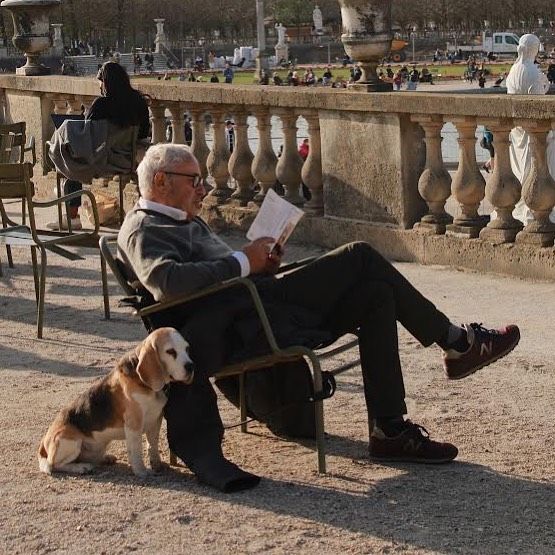

Next time you begin a project that involves creating something new, linger a little longer in the beginning. Treat that early phase less like research and more like relationship-building, a space for listening, exchange, and sense-making together. Don’t come in with the story already written; let it unfold between you and those whose lives it touches. Ask about the futures they imagine, what they’re already building toward, and what care looks like along the way. And somewhere in that process, maybe it starts sounding a little like a love letter to the future. In that kind of inquiry, stories stop being tools for persuasion and start becoming spaces for learning, places where the future can be questioned, practiced, and slowly brought into being.

That’s where the work begins.