Different ways of seeing

These are some thoughts as I step outside of my usual strategy bubble.

When feeling uninspired by my work, I love to look outside of my field for inspiration.

These photographers recently nudged me back to that place: Born Into Brothels and the spark that appears when someone is recognised; Ana Flores’ portraits that meet people as they are; and Salgado’s images that show the strength and dignity people carry, even in hard circumstances.

Together, they reminded me that meaningful work starts with attention. To people, to context, and to what’s already there.

Seeing Differently

Working at the intersection of innovation, strategy, and human-centred design in the social sector is a little like living in Amsterdam: somewhere between a city and a village. Big enough to feel expansive, small enough that you always seem to run into the same people. Meetings in rooms full of like-minded people who talk about transformation, co-creation, and systems change. Conferences with those who want a similar future to us.

And when the language starts echoing back at itself, and words start to sound like corporate jargon, that’s usually my cue to look elsewhere.

When I do, the people who inspire me most aren’t other strategists or social entrepreneurs. They’re photographers, storytellers, and people who don’t talk but show what it means to see with care.

So here are three who are currently reshaping how I think about social change and the work I do.

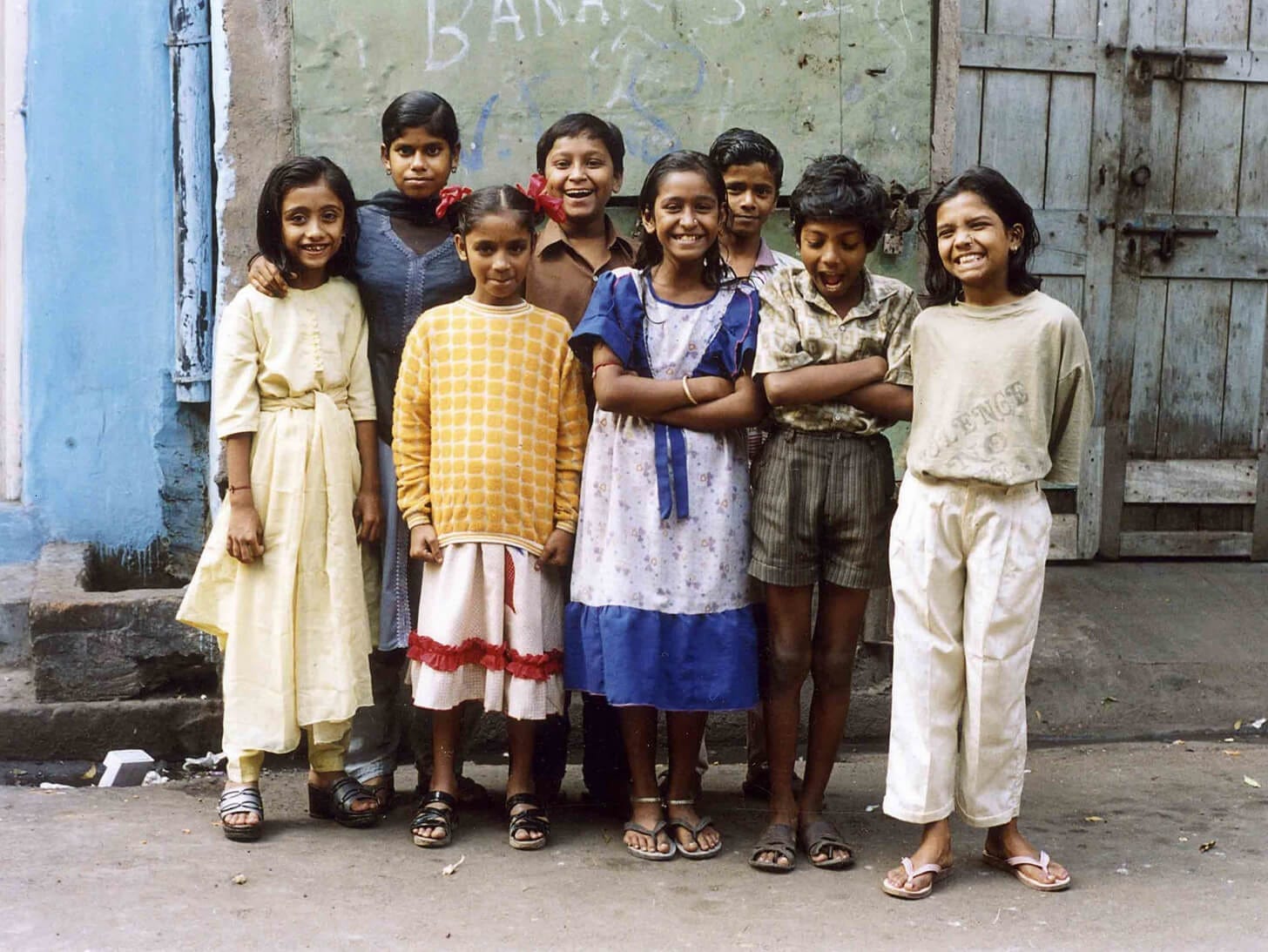

Born Into Brothels — Seeing and Responsibility

One evening in Bogotá, on a cold Saturday evening, I found Born Into Brothels (2004) on YouTube. It’s a beautiful documentary that follows children growing up in Calcutta’s red-light district — born into brothels, faced with the constant chaos of survival. Their mothers are often forced into work at a young age and are seen cursing them out; the girls are next in line to inherit the same circumstances.

But instead of only filming their lives, or that of their families, the director, Zana Briski, who is also teaching them photography, hands them cameras. The children begin to document their own worlds with amazing creativity. Their photographs reveal not just what surrounds them, but how they see, full of wit, capacity, and a vision for a future larger than what they were born into. The joy on their faces as they take, critique, and share photos with each other feels like witnessing possibility unfold in real time.

They don’t author the documentary, but they clearly shape it. The story expands to hold their perspective, not as a project of saving, but as a space where imagination and agency are so visible. And perhaps most strikingly, it shows what difference one person’s care and commitment can make: how belief in someone’s potential can become a form of infrastructure in itself.

When practitioners talk about rethinking social design, they explore the concept of agency, and I think felt is that Zana Briski created a beautiful way for these children to start their exploration of that.

She not just saw, but also showed these kids the full capacity to imagine, create, and contribute. And was able to share this with the audience. Born Into Brothels reminds me that change often starts there: in the simple act of recognition, and in the relationships that allow people to believe in their own possibilities.

Sometimes the most meaningful shift is when people are seen, not for what they lack, but for what they contribute, imagine, and are.

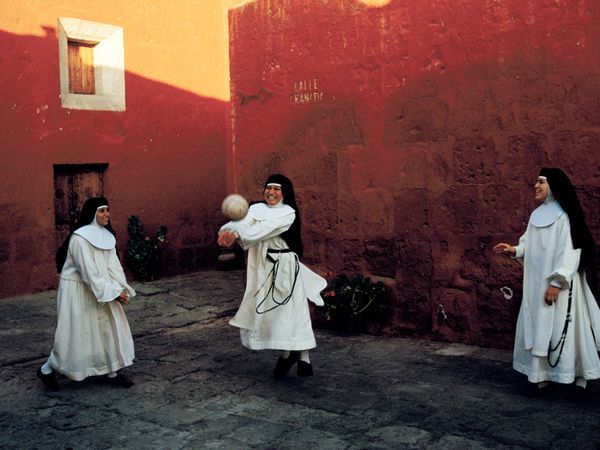

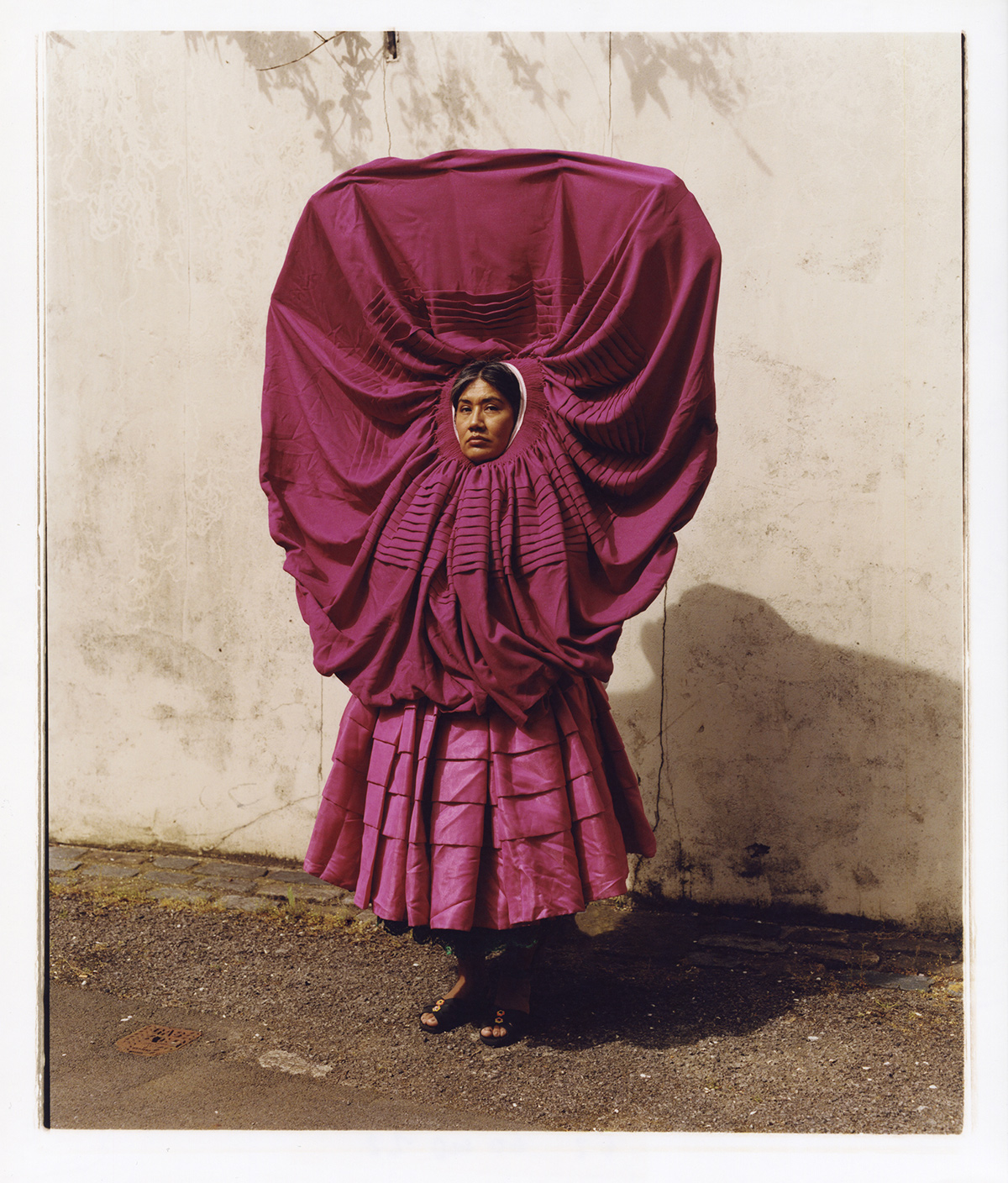

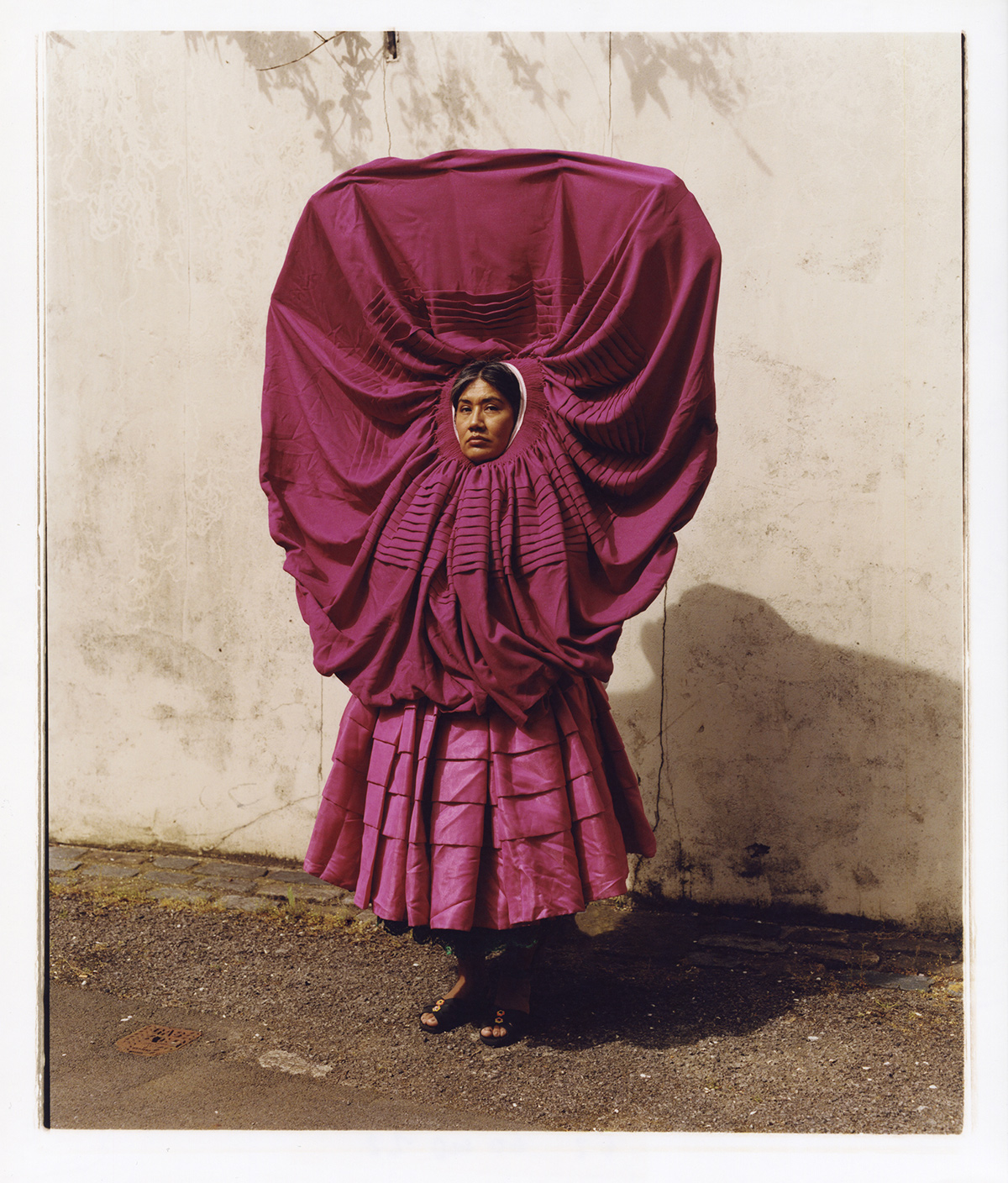

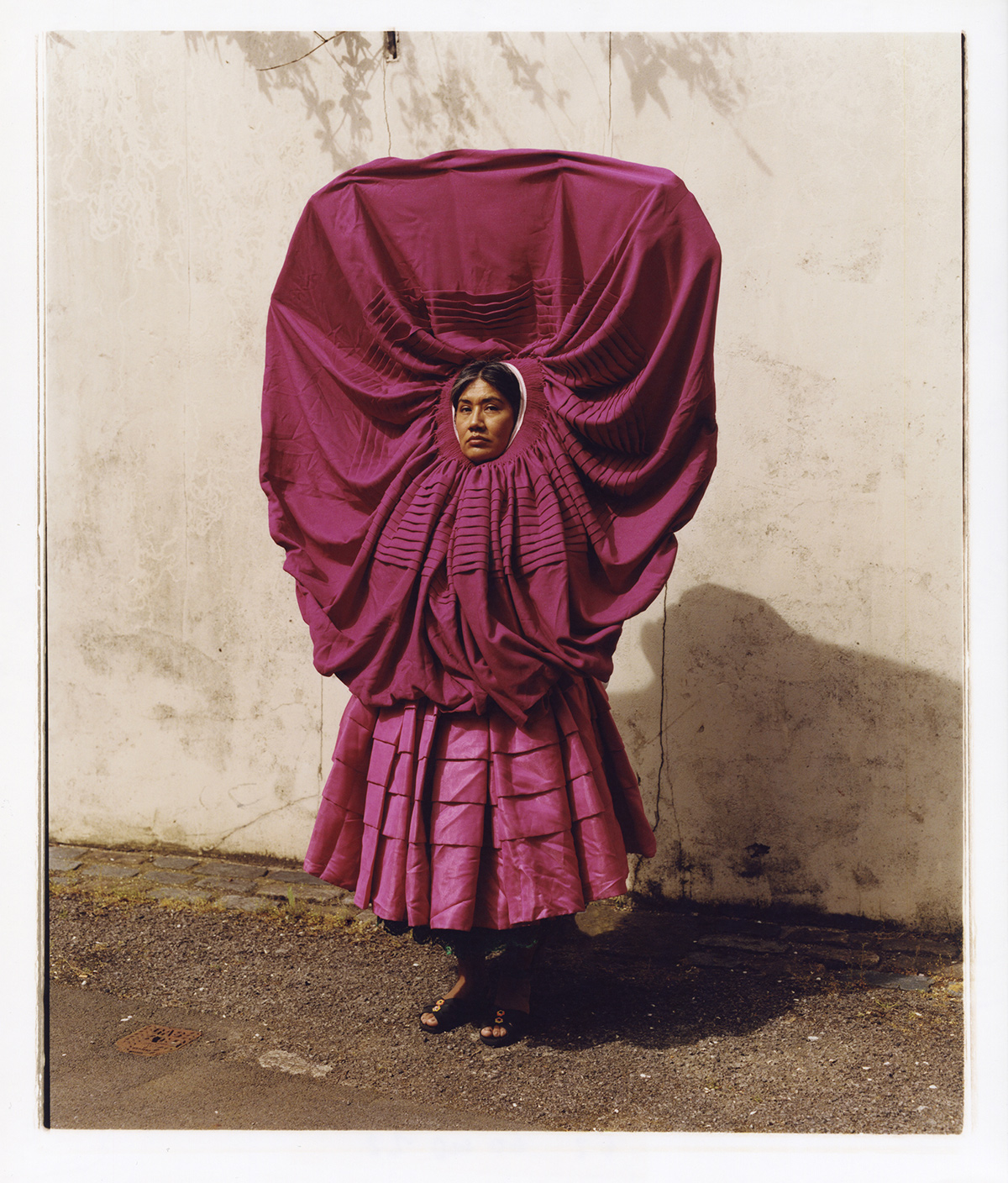

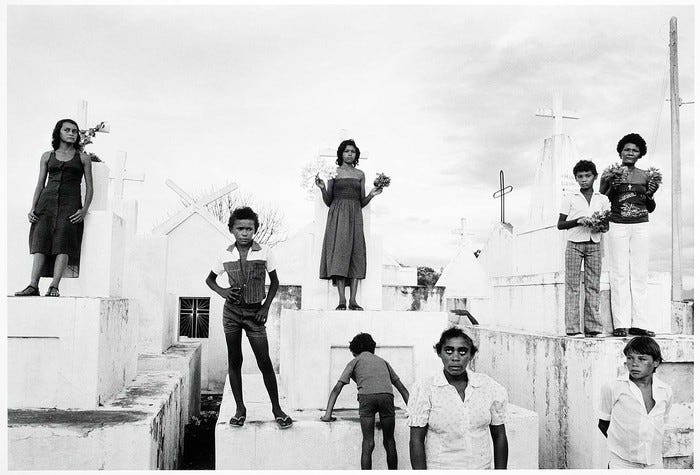

2. Ana Flores — Returning Authorship

Ana Margarita Flores’ Donde Florecen Estas Flores (Where the Flowers Bloom) is a striking series of portraits of Andean women, not captured as distant cultural symbols, but very much as contemporary, present individuals.

What I love about her work is how it cuts through the usual layers of interpretation. These portraits don’t treat the women as representatives of a culture or an idea; they meet them as people. Their presence feels direct, intentional, and fully their own.

And that’s the reminder I take into my own work.

Whether we’re working in design, strategy, or storytelling, it’s easy to focus on context, systems, or circumstances and forget the person at the centre of it all. Flores’ portraits nudge me to look past the category I might instinctively place someone in, and to pay attention to who they are beyond the frame I’m tempted to use.

So I keep a few questions close:

- Does my work reflect someone’s full dignity, agency, and complexity, or am I unconsciously reducing people to a narrative?

- How would my perspective change if I were personally affected by this issue? What assumptions might shift?

- How has my background shaped what I notice, and what I overlook?

- Would I feel comfortable sharing this story with the person it’s about? Would it reflect how they’d want to be seen?

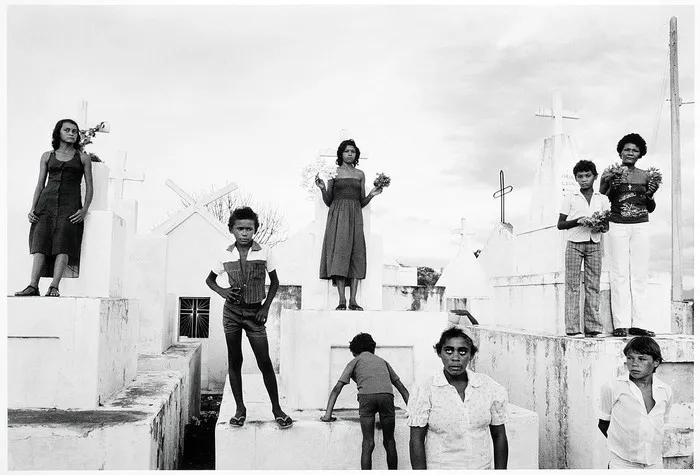

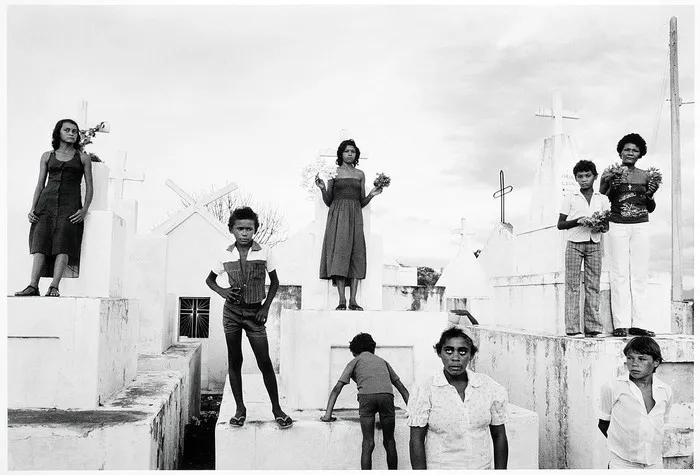

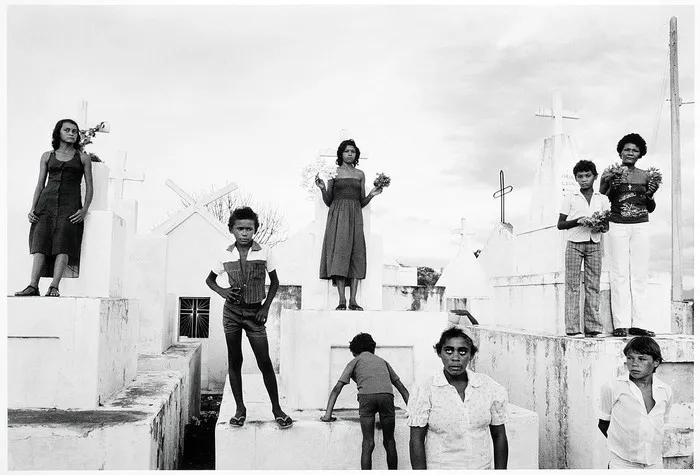

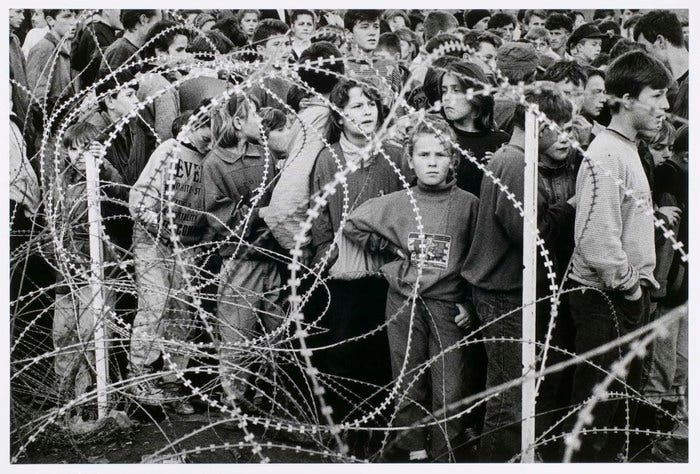

3. Sebastião Salgado — Dignity and Repair

Salgado once said, “ I never photograph the misery.”

His work has inspired a generation of photographers, even as it’s been debated for how it navigates the line between art and suffering. What stays with me, though, is not the hardship in his images but the dignity and endurance that run through them.

His photographs don’t just document circumstances; they reveal the strength people carry within them, even in the most difficult environments.

And that matters for how I think about social change.

When we’re designing or strategising for impact, where are we looking for direction? Are we only mapping problems, or are we paying attention to the forces that already help people endure, adapt, and support one another? Where are the small pockets of energy in a system — the places where a shift could unlock something larger? How might the structures we build either reinforce or suppress the capacities that communities already hold?

It’s easy to focus on deficits; it’s harder to sit long enough to see the full picture — the care, the networks of reciprocity, the human priorities that keep people moving forward.

Salgado reminds me that empathy isn’t soft. It’s a discipline: staying with the complexity until you can see the person beyond the moment of crisis, and designing from that place.