Close enough to care

On the quiet work of closing the distance between people and planet.

Exploring why climate change feels so hard to act on. Not because we don’t care, but because it feels distant: in time, place, relevance, and certainty. That distance keeps us from turning concern into action. Humanity, stories, empathy, and emotions may help close that gap. They make the abstract human, the faraway close, and could make the future feel like it belongs to us. Facts inform us, but stories move us, and maybe that’s where meaningful change begins.

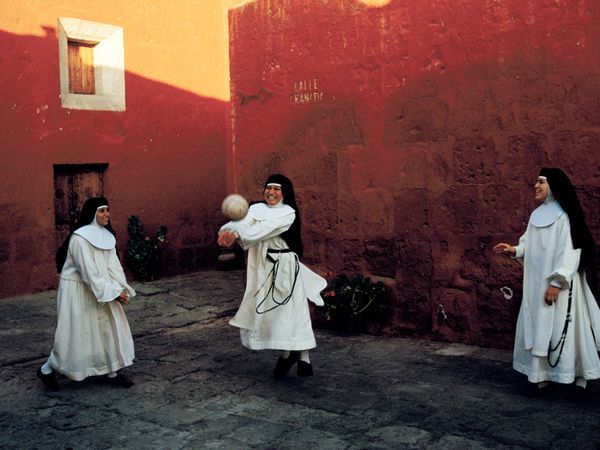

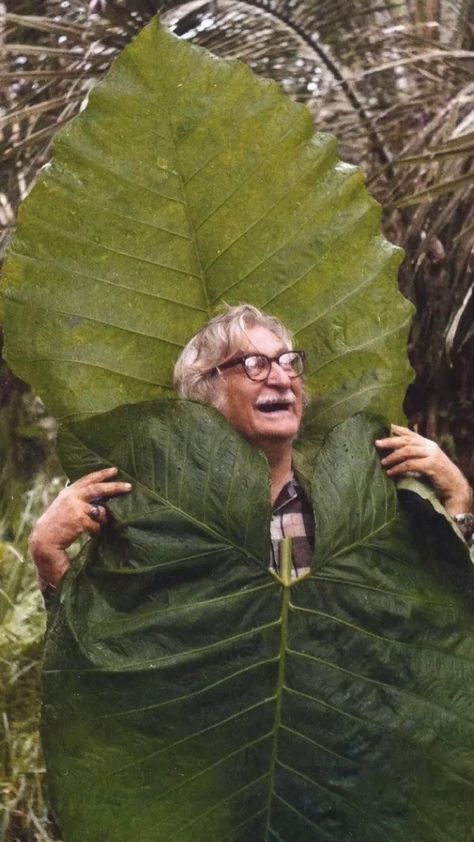

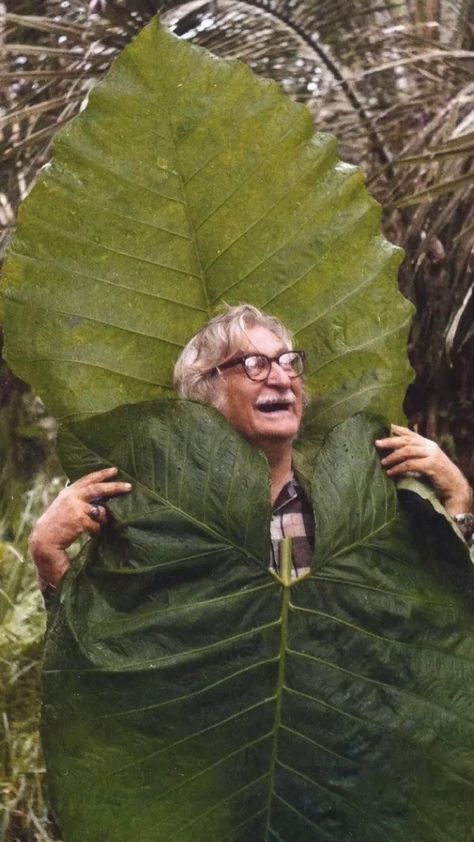

“The greatest danger to our future is apathy.” — Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall, ethologist, conservationist, humanitarian, and icon, who passed away recently at 91, led a life of incredible purpose. A life defined by attention, compassion, and a stubborn belief in our capacity to change.

“Here we are, the most clever species ever to have lived. So how is it we can destroy the only planet we have?”

To me, her words feel heavier now than they did back then. In part because of the urgency that surrounds climate issues today, the natural disasters and a lack of political support worldwide. But in large part, because regardless of how obvious the signs are, our behaviour doesn’t reflect it. How little it seems to move us.

And if we do care well, then it hasn’t turned into the kind of collective momentum that complex change demands. Not yet, at least. That care hasn’t grown into something shared, a way of living and seeing the world together; the kind that shows up in our habits, choices, and systems.

I’ve thought about the why behind this a lot, looking at my own behaviour, and that of those around me. The conclusions have been many because I don’t think there’s an easy answer. But the one that’s stayed with me is this: the problem is simply too complicated, too tangled, too systemic. And the solutions — well, those still feel far away, undefined, uncertain, and slow to pay off.

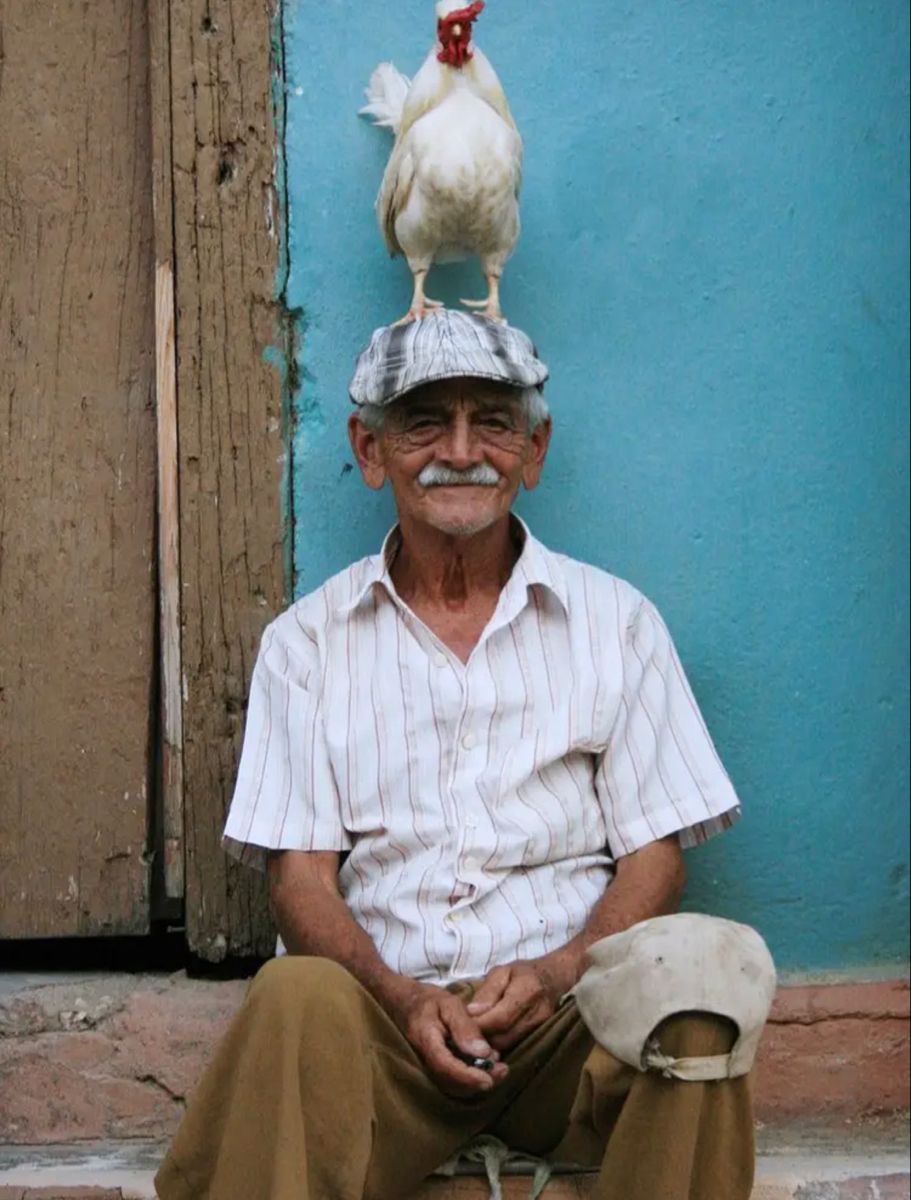

And so, life circles back. We fall into our habits, and we forget until the next reminder.

A problem of proximity

If there’s one thing that I have learnt studying human behaviour, it’s this: we’re often just not that rational. That means our actions are neither. And I think that matters a lot when we talk about climate change.

If our behaviour were then, the challenge ahead of us as a species might not be that hard. One reason we struggle to respond might be because of something called psychological distance.

Psychological distance is how far something feels from our own (lived) experience. That is, distance either in time, in space, in social relevance, or in certainty. The further away it feels, the harder it is to care in a way that drives action.

Distance in time

Climate change is often framed as a “future problem.” Mass migration, failing crops, rising seas — decades or centuries ahead. That makes it easy to put off, because the human brain is wired to prioritise what’s right in front of us.

Distance in space

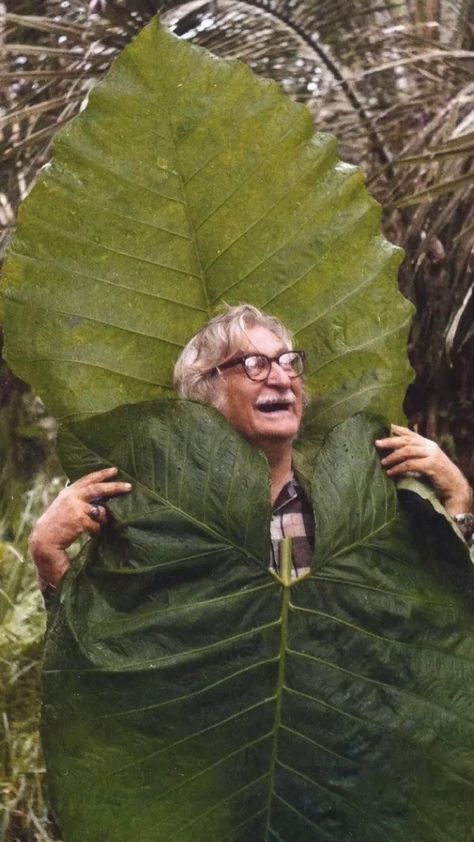

We often see climate change in images from faraway places: deforestation in the Amazon, Himalayan glaciers melting, and Australian bushfires. Disasters that feel like they belong in a documentary, not in our own neighbourhood. That distance makes it feel like someone else’s problem.

Distance in social relevance

When flooding hits Pakistan, or a heatwave scorches India, it lands in the Western world with a sense of otherness, as if these lives, these losses, belong to a different moral universe. But the atmosphere does not recognise borders, and neither do the systems that sustain us. Their heatwaves write our weather patterns; their floods shape global markets; their ruined crops ripple into the food we buy. As writer Arundhati Roy reminds us, “There’s really no such thing as the ‘voiceless’; there are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard.” Climate suffering often becomes the “preferably unheard,” held at a distance to protect our illusion of separateness.

Distance in certainty

Climate science deals in probabilities and ranges: likely scenarios and confidence intervals. When we hear “temperatures may rise by 2–4 degrees,” we treat that uncertainty as a reason to delay, even though the overall direction and severity are beyond doubt.

And as researcher Taciano Milfont points out, these four dimensions feed each other, widening the gap between knowing and doing.

But the distance isn’t only in our minds; it’s built into the systems around us. Economies depend on endless growth, as if infinite resources could come from a finite world. Technology rewards immediacy, even as we grow more disconnected from what gives us depth.

It’s not only that people don’t want change. It’s that the structures we live within make sustained attention, and therefore sustained action, incredibly hard. Shaping not just how we act, but how we see. What feels urgent and possible. What we believe will matter.

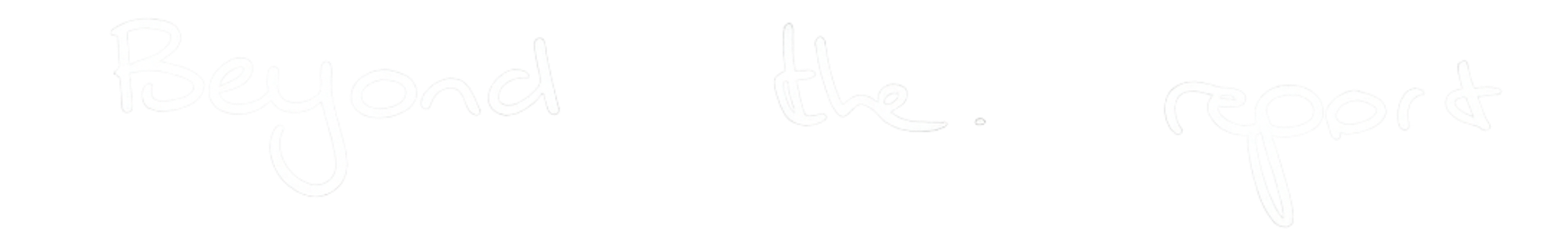

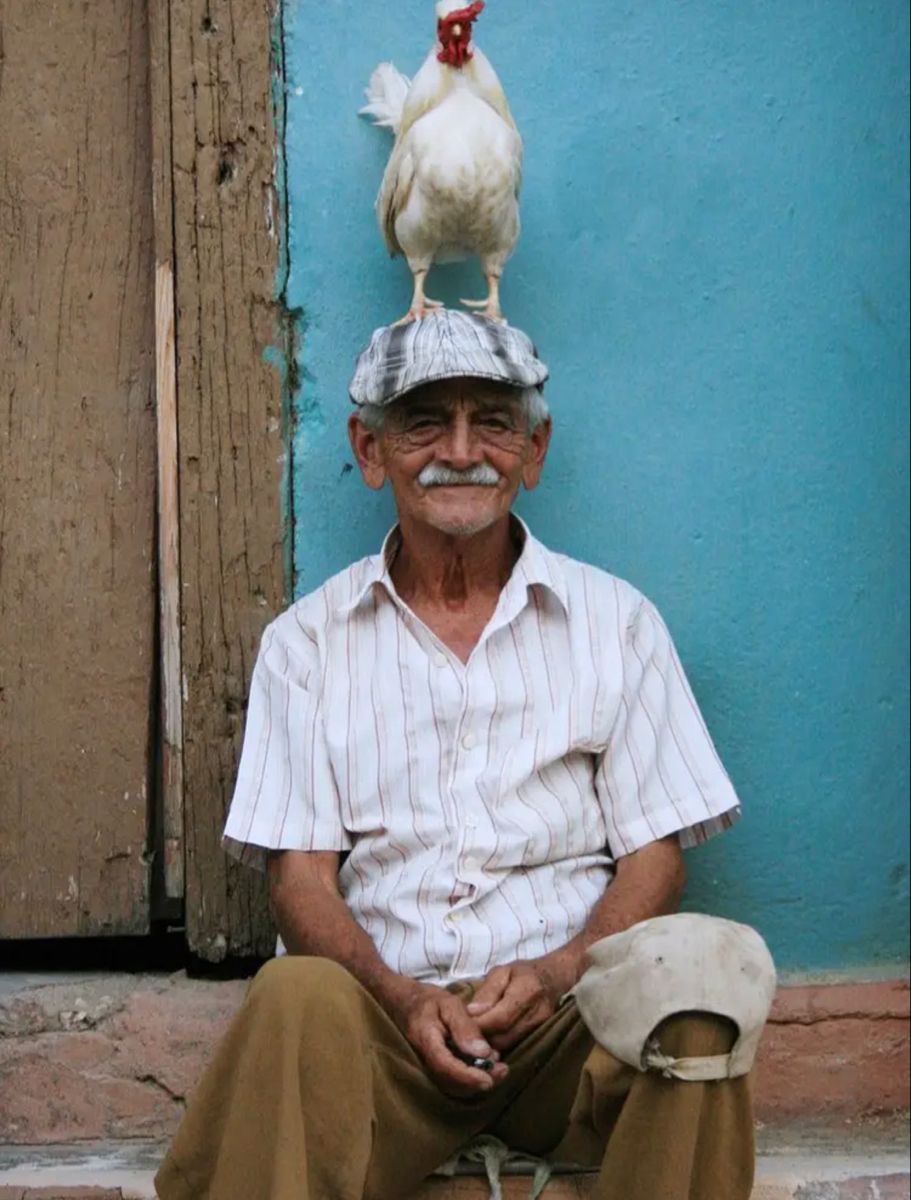

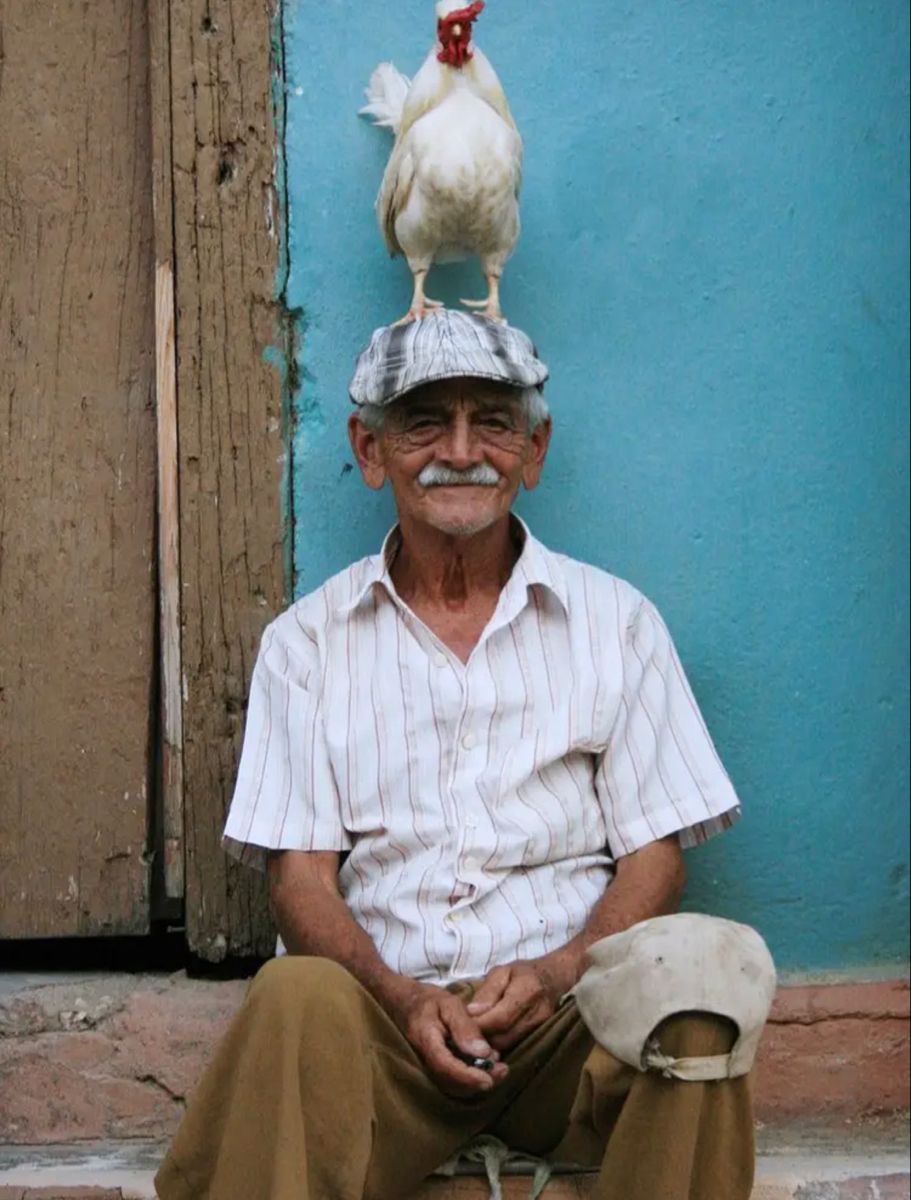

Stories let us inhabit another person’s experience for a moment. They draw the outlines of their world so we can walk inside it, if only briefly.

They shrink the distance between them and us, between the present and the future, between what is and what could be.

Shrinking that distance

If data gives us the facts, stories give us the feeling. They help us remember what it means to care. A story can make the faraway feel near, the abstract, suddenly human, reminding us of all that we share. The routines of everyday life, the fragility of what we love. Stories work because they close the gap, making the invisible visible and the distant familiar.

They remind us that climate change isn’t happening somewhere else, to someone else. It’s happening here, to all of us.

The Psychology of Storytelling

There’s a reason stories reach us in ways facts can’t. Data sits in the part of the brain built for words and structure. A story moves beyond that, touching the regions linked to sensation and emotion, where memory and meaning meet. So that simply understanding something becomes experiencing it.

Neuroscientist Uri Hasson found that during storytelling, the brain of the listener actually begins to mirror the storyteller’s. And as it begins to mirror the storyteller, their patterns sync. For a moment, two people think and feel in the same rhythm.

Stories work because they make us feel what others feel. They pull distant lives closer until the gap between “them” and “us” starts to blur. That’s where change begins, in the lives we begin to imagine as our own.

But stories do more than move us; they help us make sense of what’s otherwise too vast to hold. They take something abstract, like climate change, systems collapse, collective responsibility — and translate it into something we can feel, name, and remember. They give shape to what might otherwise stay invisible.

As cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner once said, we don’t just use stories to entertain; we use them to make sense of the world. They turn chaos into sequence, overwhelm into understanding.

Stories alone won’t solve climate change. But they can make it harder to look away. When we see the crisis reflected in human lives, we begin to understand that this isn’t just a planetary story; it’s a personal one.

That may be Jane Goodall’s enduring gift to us: not just her science, but her insistence that empathy is a form of action.

If apathy is the greatest danger to our future, then connection, seeing ourselves in each other’s stories, might just be its cure.

Change begins not in the data, but in the stories we choose to tell and believe. Because once we begin to feel the future as our own, we can no longer stand still.

Maybe that starts in smaller places, in how we talk about our work, the choices we make, and the attention we give. In daring to tell stories that stretch beyond our own comfort, even inside systems that reward the opposite.

If stories are how we make sense of the world, then perhaps the work ahead is to make sense differently, to build narratives that remind us what’s worth protecting, and who we still have time to become.